This work is a theoretical reflection on leisure and identity whose confluence is materialised in a practical proposal. The project builds the opportunity to recover a dignified leisure space in a neighbourhood that has been mistreated, isolated and abandoned to its fate. The decisions taken to shape this proposal are based on the imagination of an alternative future in which new scenarios are built that are more empathetic to the environment and to the social reality of a collective.

The Site and the Neighbourhood

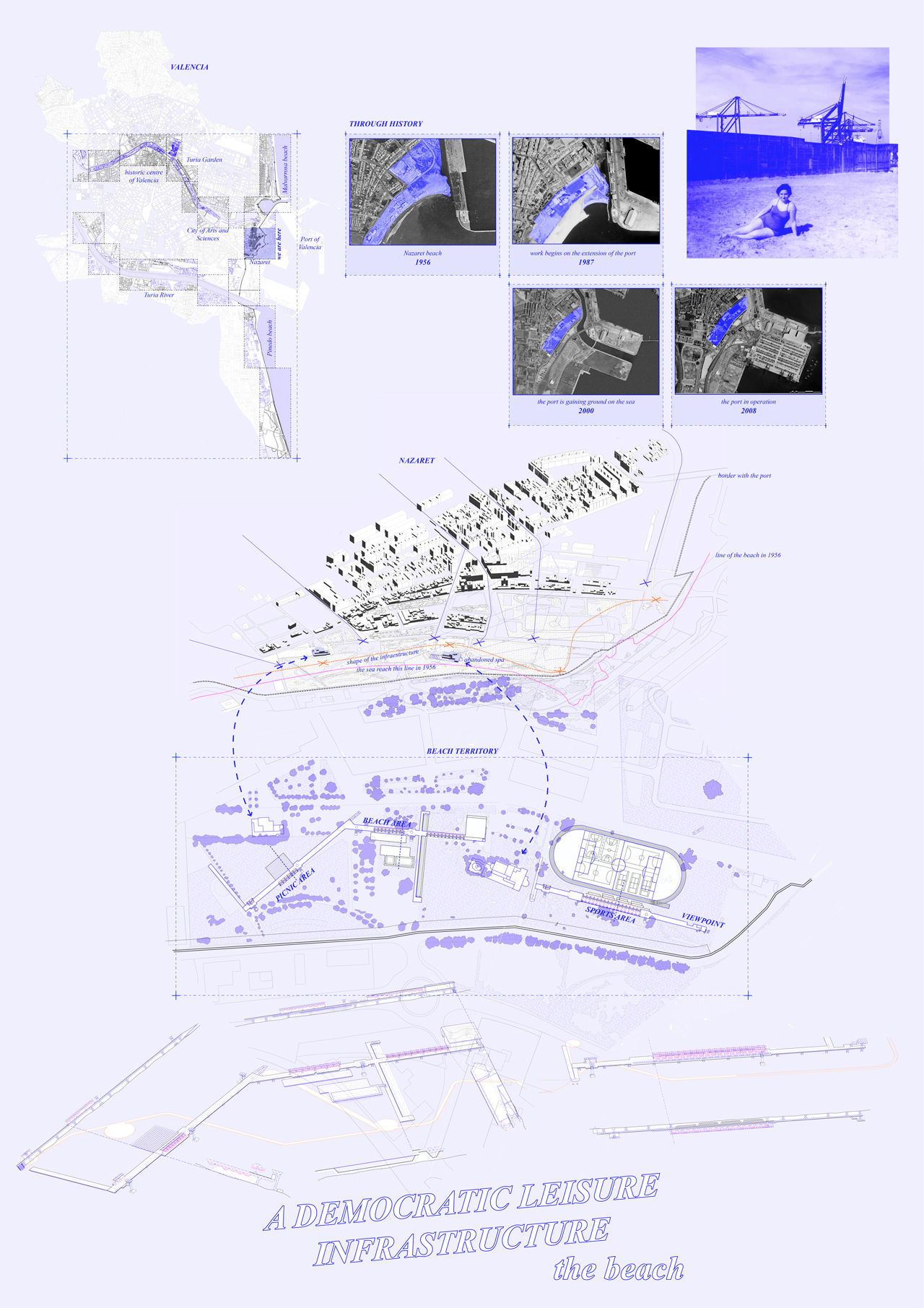

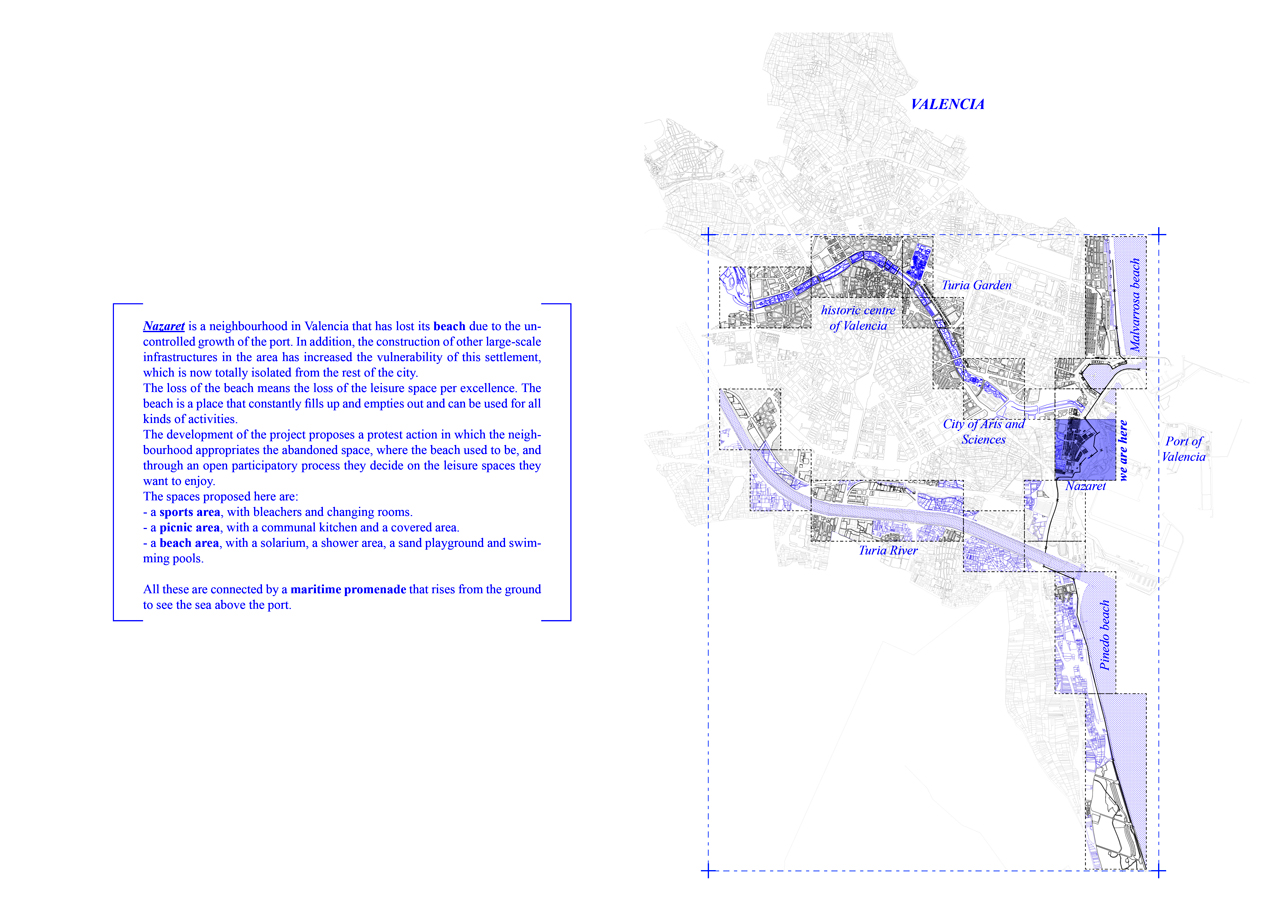

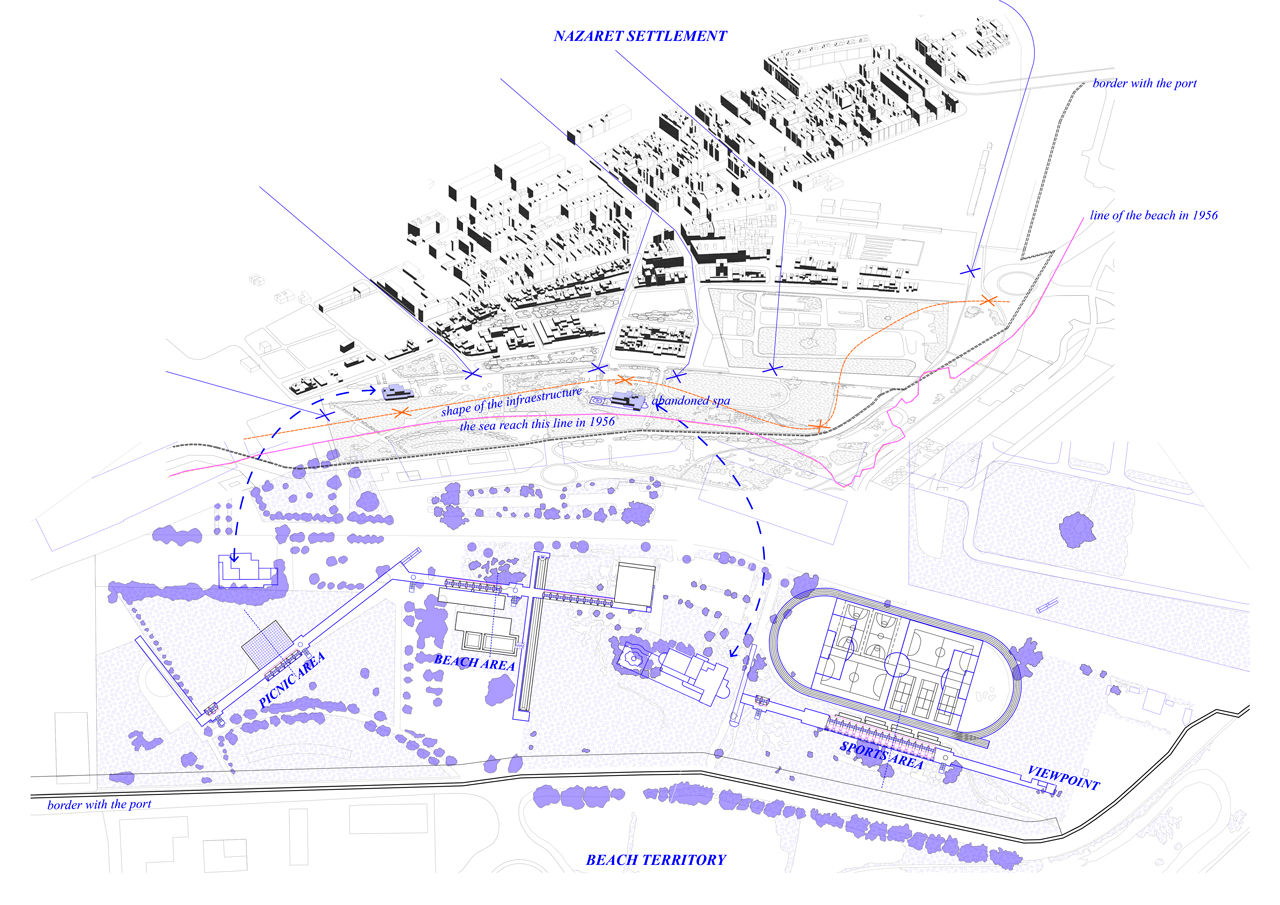

Nazaret is a neighbourhood of the city of Valencia that originated at the beginning of the Eighteenth century linked to the sea and the city’s farmland. During the first half of the Twentieth century, the need arose to modernise the Port of Valencia in order to make it a competent centre for Mediterranean traffic. This was an opportunity to activate the economy of Nazareth by housing warehouses and industries related to port activity.

A second process in the economic activation of Nazareth includes this time social dynamism. Mirroring what was happening elsewhere in Europe, Nazareth also saw the spread of a leisure resource that colonised the beaches. Because of this progressive development of society’s interest in the coastline, summer villas and leisure facilities were built, and, in summer, picnic areas and bathing huts were set up on the shores. Well into the 1950s, the neighbourhood experienced its best years in socio-economic terms thanks to the consolidation of its beach as a leisure area.

These years of progress came to an end due to the uncontrolled growth of the Port combined with the developmentalism of the Seventies, which favoured a growing process of deterioration and geographical isolation of Nazaret. New infrastructures were built, such as the Saler motorway and a new railway line, polluting industries were established in the town centre, and therefore the old riverbed became a drain for the city as it passed through the neighbourhood, polluting the Nazaret beach and making it impracticable. This first process of degradation of the beach and the consequent loss of attractiveness for visitors was followed by the process of expropriation of the use and enjoyment of the beach as a public space by the Port of Valencia, ensuring jobs for the people of the neighbourhood in exchange, which was not fulfilled. This way of proceeding, and from the perspective of experience, is clearly identified as a speculative strategy.

Nazaret is today one of the most impoverished neighbourhoods in the city of Valencia and undoubtedly the most marginalised. There is considerable local discomfort due to the isolation and the disastrous management of the municipal and autonomous government of the early 2000s, which far from dealing with the social problems of the neighbourhood, such as the lack of work and leisure opportunities, decided to focus on the politics of big events such as America’s Cup or Formula 1, which isolated the neighbourhood even more.

Due to so many years of mistreatment, the inhabitants of Nazaret have one of the worthiest associations in Valencia that defend the identity of a maritime neighbourhood with a lot of potentials. Undoubtedly, an important part of the identity of the Nazaret neighbourhood has taken shape because of what the beach once meant to the neighbourhood in terms of well-being. In this confluence between the beach as a leisure paradise and the construction of an identity that arises from the loss of this space, a project is born that aims to dignify the struggle of a neighbourhood. What is a maritime area without the sea?

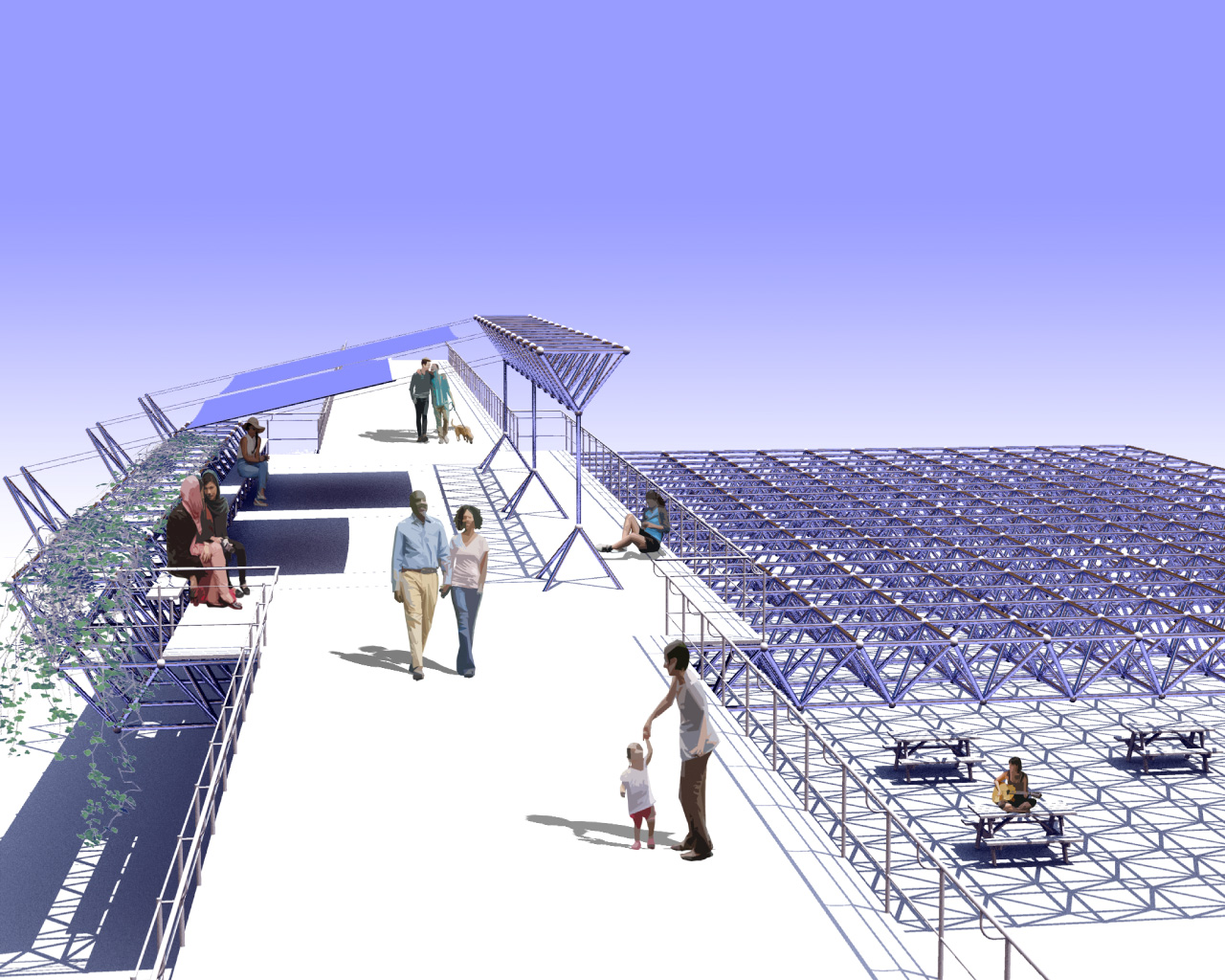

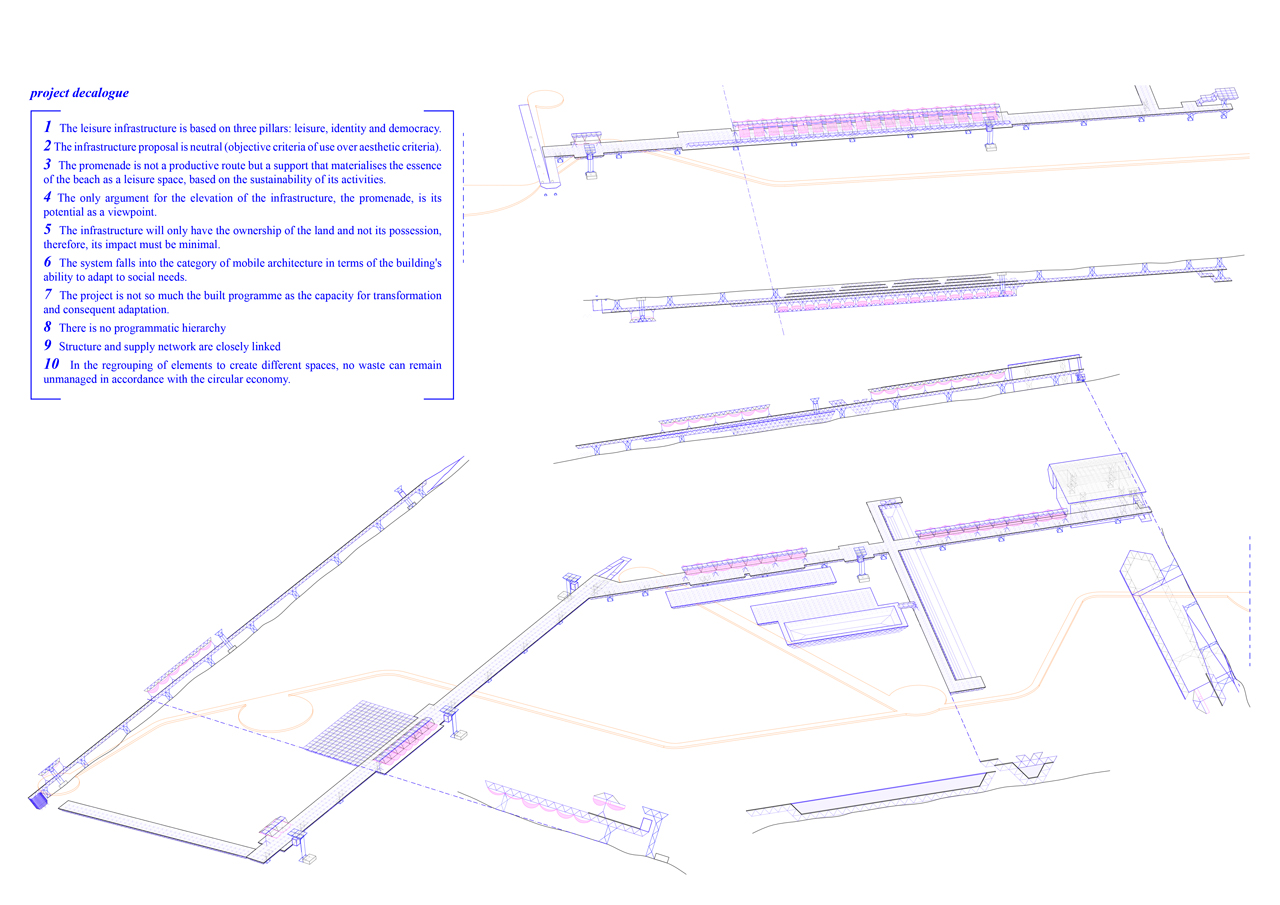

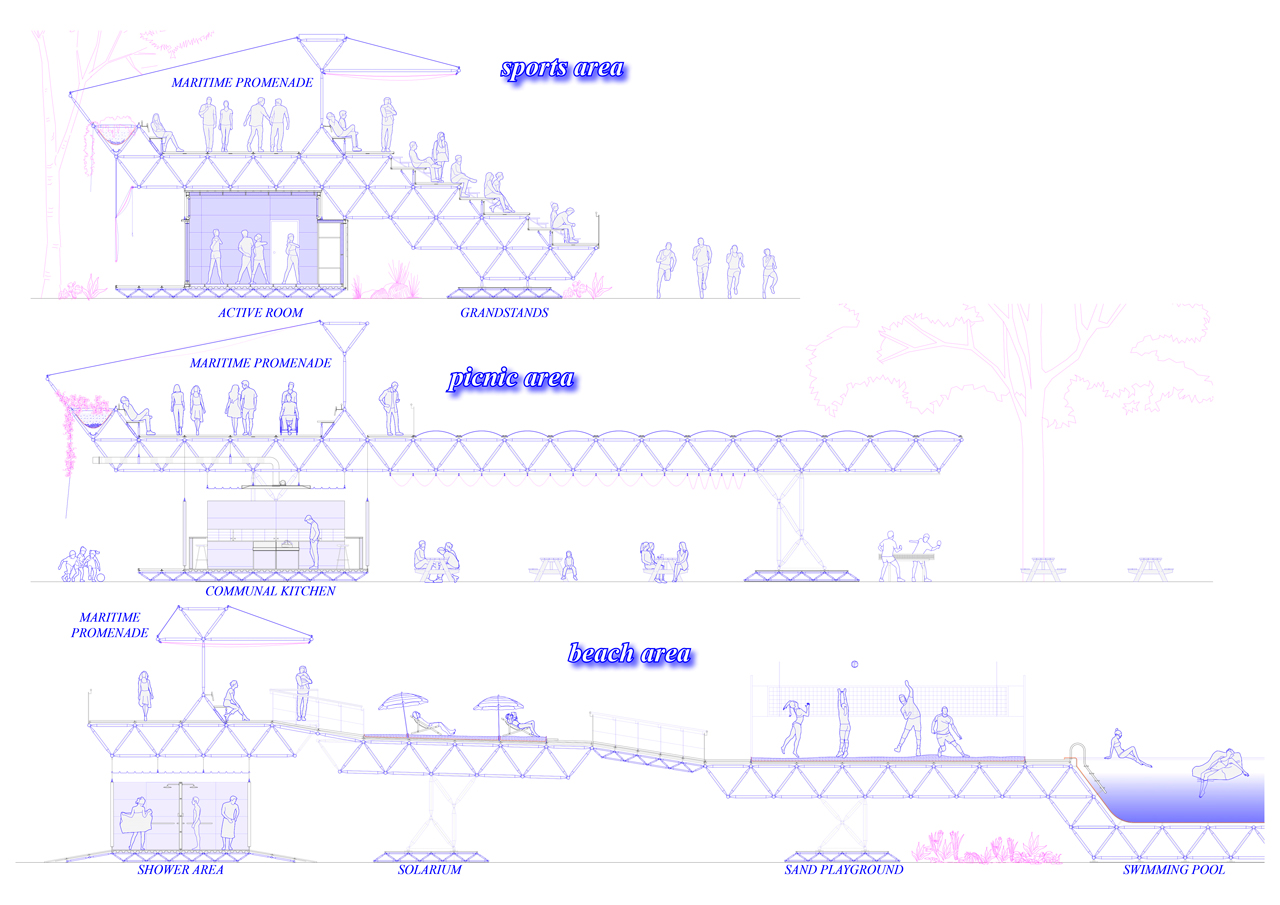

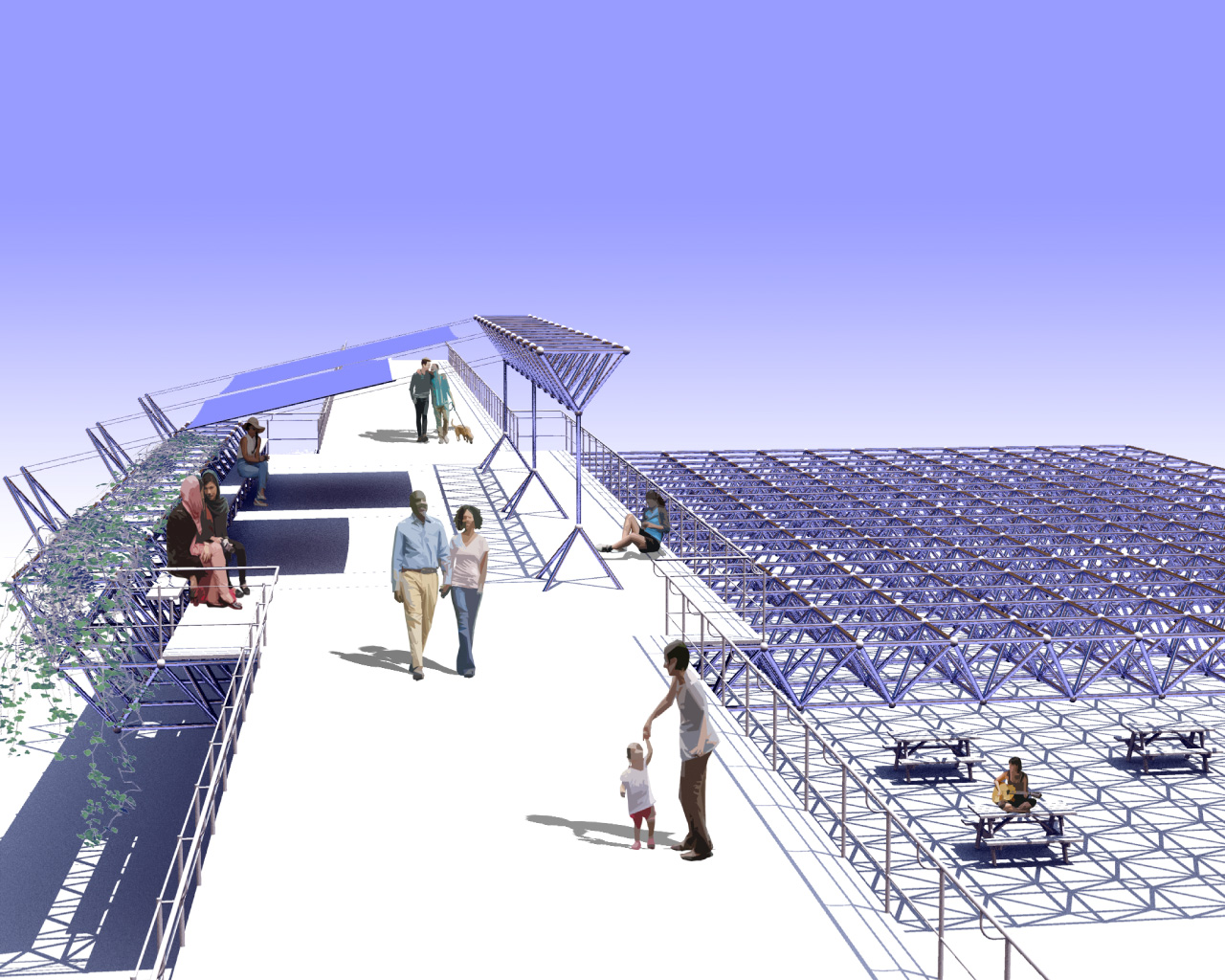

The neighbourhood needs to reclaim the beach that was once stolen from them. They have to occupy the space and build with their own hands the beach that belongs to them. This is the reason for the phased construction of a seafront promenade that rises from the ground to stand above the port and works as a viewpoint towards what belongs to the local community. The promenade will connect or contain the different activities that can take place on a beach – rest, sport, water and leisure.

The Design Proposal

As a society, we recognise the right to leisure, although it is always linked to the concept of work. Leisure, understood as the use of free time in the pursuit of pleasure, is in dispute between the essence of pleasure itself, erratic and subjective, and what the system offers as a promise of enjoyment. This offer translates into the commodification of the territory to stage a mirage of leisure, to maintain a relatively satisfied workforce to compensate for the frustrations of people’s everyday lives. The more aggressive the staging of this leisure, the more the system profits and the more the social inequalities of the city of pleasure become apparent. The only way to escape the illusion of pleasure is to build a democratic framework, constantly reviewed and adapted to user demand, in which leisure is not a profitable commodity.

The difficulty lies in the materialisation of a space of pleasure through architecture. Lefebvre said that the construction of a space dedicated to pleasure has to free itself from pre-established norms and the definition of uses. Any exact definition of what provides pleasure is attributed to the alienation of the population to make one more aspect of society profitable. Pleasure does not respond to norms but is subjective to everyone. Architecture will not aim at pleasure but at making it easier for the person to find it. How can we offer an architectural framework that facilitates the encounter with pleasure?

The answer is transfunctionality. The constructed space of pleasure will be constantly revised and adapted to the social needs of each moment. This can be a utopia in a world founded on the “eternal”: property, marriage, religion, the state, are the social formations that govern today’s society and are conceived from the perspective of eternity, constructing social rules from this angle. From this intransigent premise, social conflicts arise due to the inability of institutions to take on board the nature of everyday life: change.

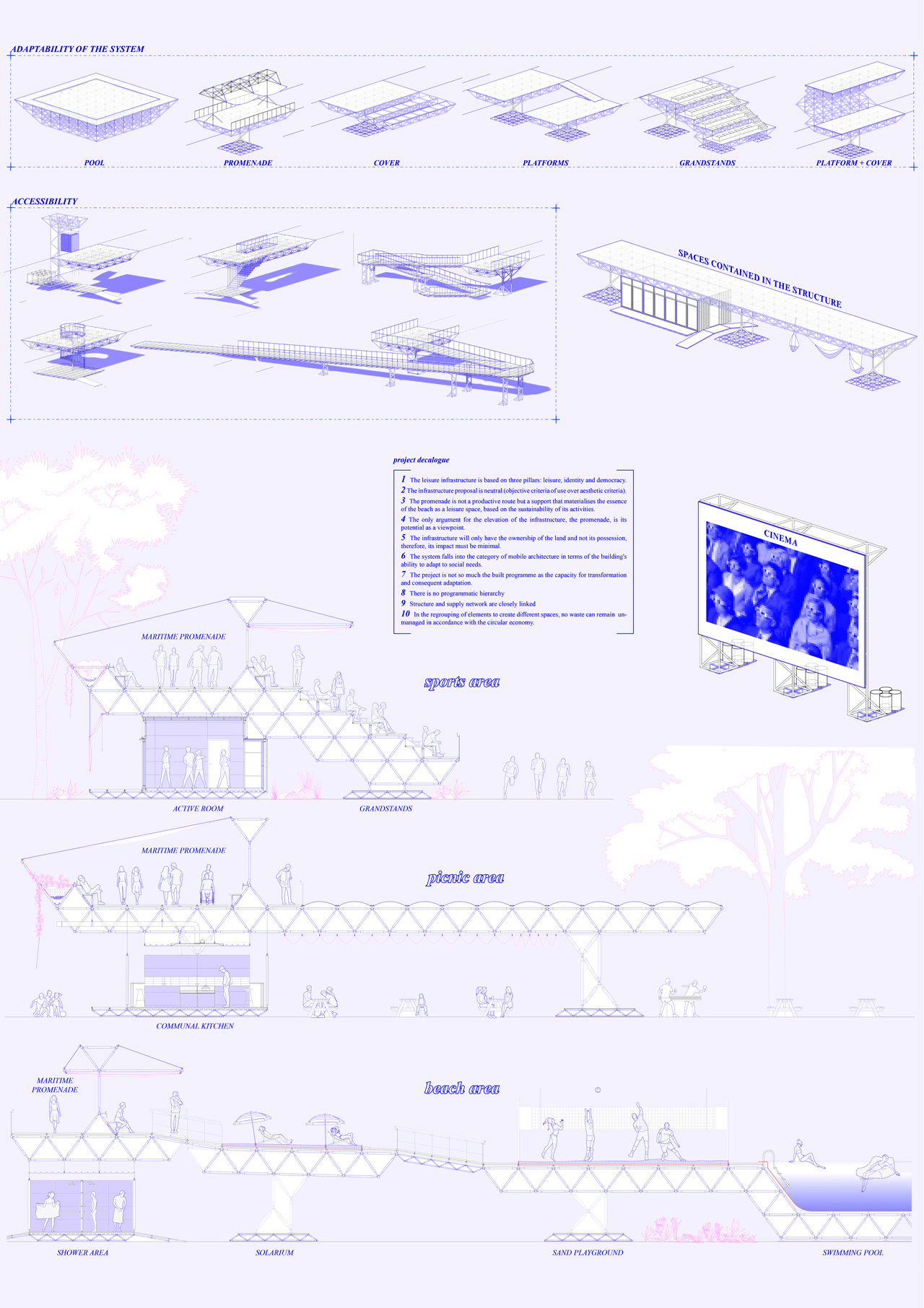

The architectural answer to transfunctionality was proposed by Yona Friedman in 1958 in the manifesto “Mobile Architecture.” He proposed a neutral and stable but continually changing infrastructure that responds to social needs. The spatial structure that he suggests makes it possible to continually rethink spaces thanks to the fact that it is made up of small elements (bars and nodes), which are easy to manufacture, transport, store, assemble, disassemble and reassemble to build a new space. This type of dry construction is environmentally sustainable as it can be included in the processes of the circular economy.

What makes this open infrastructure consistent with the reality of the inhabited space, Nazaret, is its materialisation as a seafront promenade, recovering the essence of the beach which once gave identity to the Nazaret neighbourhood. Thus, building spaces such as swimming pools, sandy beaches, terraces, grandstands and relaxation areas, among other things.

The proposed system considers the fragility of the coastal environment it inhabits. In order to facilitate its adaptation to possible changes derived from the dynamics of climate change, it was decided to generate the least impact on the land by proposing a dry foundation on the surface, as well as guaranteeing maximum permeability of its soils so can manage possible future natural risks.

The project is not so much the construction programmed as the capacity for adaptation. The aim is to express the versatility of the proposed system. It is an open system of unfinished assembly capable of generating interaction between the proposed spaces and people. After all, the form of the infrastructure and the spaces generated must emerge from a democratic process at the neighbourhood level.

Technical conclusion:

- A technique which makes it possible to build temporary agglomerations so that their regrouping does not entail the material losses of “demolition.”

- Structure and supply networks are closely linked.

- Inexpensive elements in relation to their capacity for assembly and disassembly, ease of transport and conditions for reuse.

The Jury

“The project proposal addresses the theme of a neglected beach with an original point of view, and the context of the intervention is well researched and expressed. The re-activation is imagined through a Friedman like infrastructure that can be built together with the neighbours.”

“The project has a solid theoretical support, and the urban context research was deeply nourishing for the relevance of the proposal in terms of use and appropriation for a space that people lost over time.”

“The call opens to the possibility of urban landscapes projects. Within this scale of intervention, the building system, the materiality and modularity make the proposal assume low-cost characteristics but still with a high total cost and long-term existence.”